Delivery Preferences:

Student Surveys and Institutional Responses

21

Organizations

≈100k

Students

41

Reports

Thematic Analysis

This thematic analysis looks for patterns and trends in survey reports and from the key informant interviews that are related to student preferences on course delivery methods in education, particularly focusing on in-person, online, and hybrid learning formats. By analyzing survey data, institutional reports, and student experiences, this thematic analysis discusses key factors influencing students’ choice of modalities, such as flexibility, engagement, accessibility, and academic performance.

The COVID-19 pandemic catalyzed a rapid shift to online learning, compelling institutions, students, and faculty to rapidly adapt to virtual education. This transition highlighted the strengths and weaknesses of different learning modalities, as well as the evolving preferences and challenges faced by diverse student populations. While online learning offered unprecedented flexibility and accessibility, many students, instructors and institutions struggled with the limitations and changing landscapes of virtual environments.

Click the data spotlight slides in each sub theme to navigate to the source report in the repository.

Institutional Adaptations

Instructor Preparedness and Familiarity

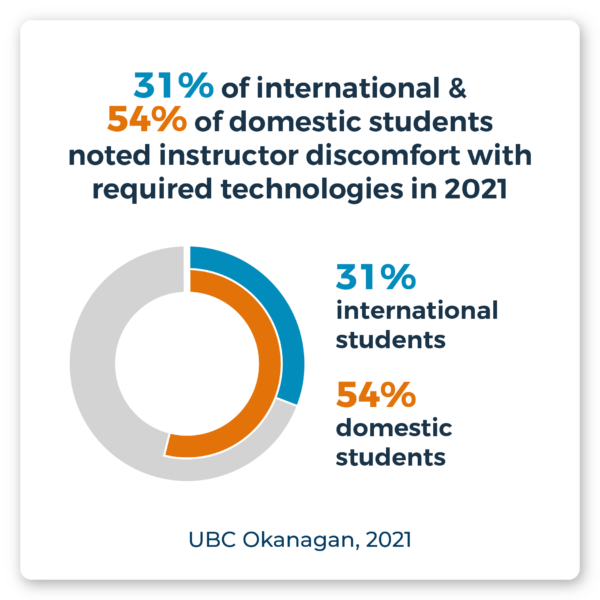

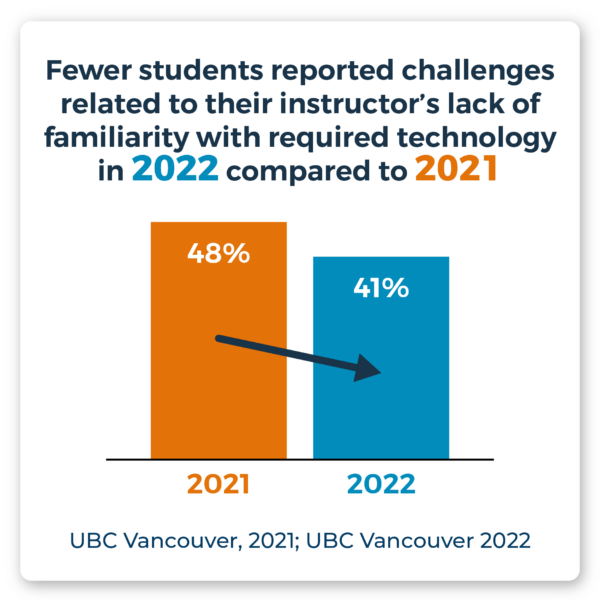

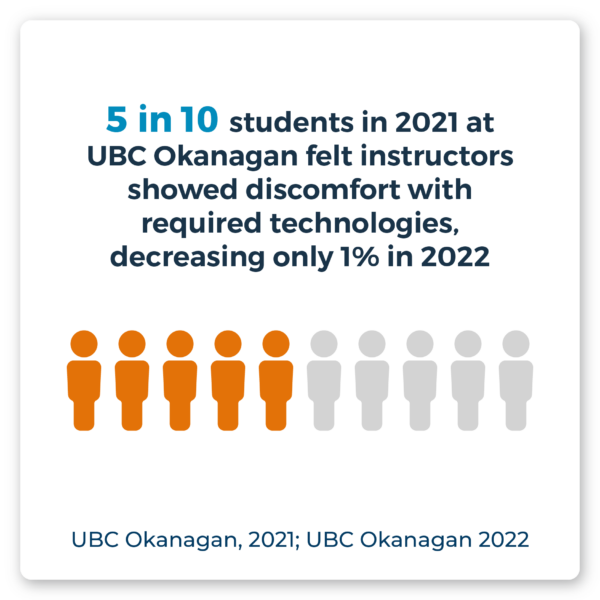

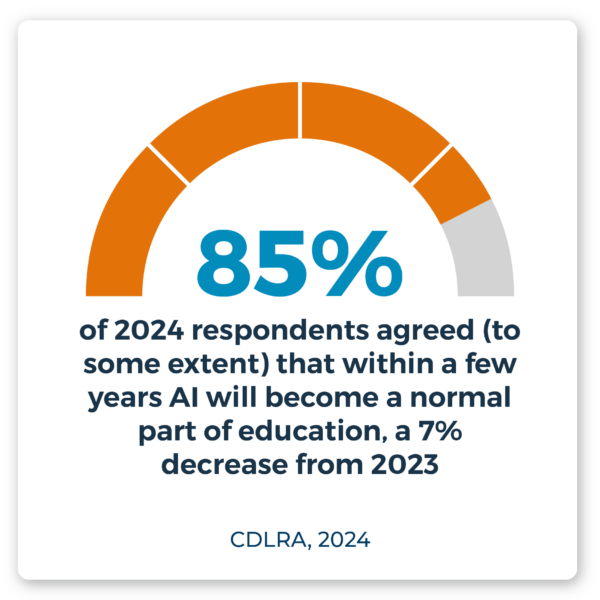

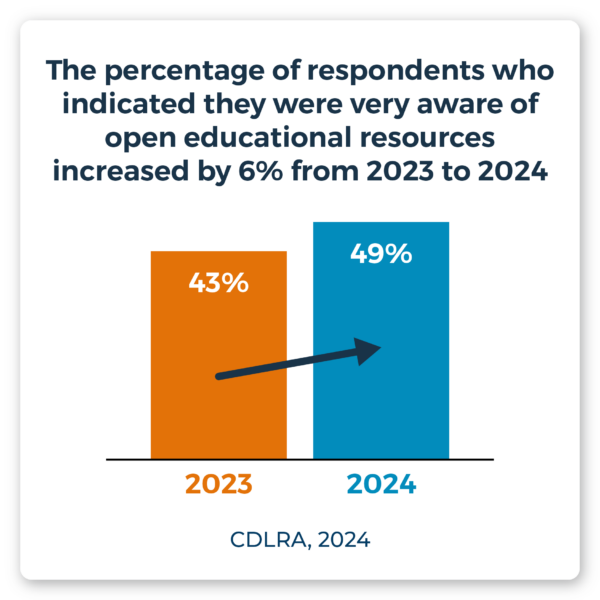

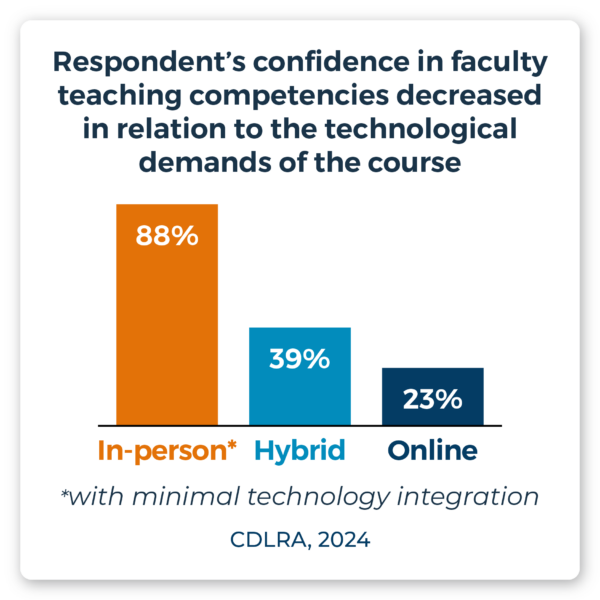

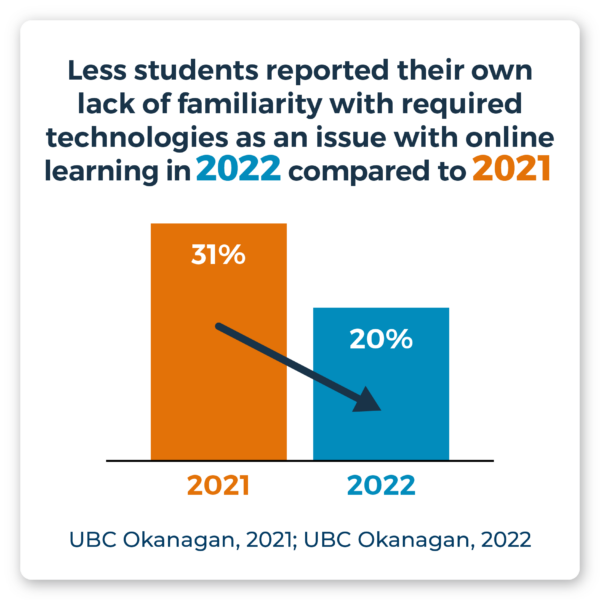

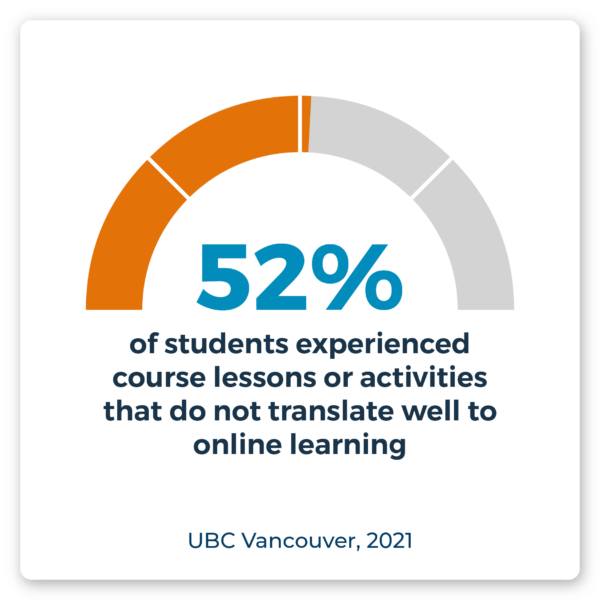

Faculty preparedness significantly influenced the experience of online and hybrid learning. At UBC Vancouver, 48% of students in 2021 reported “instructor discomfort or lack of familiarity with required technologies or applications”, a figure that improved slightly to 41% in 2022 (UBC Vancouver, 2021; UBC Vancouver 2022). Similarly, at UBC Okanagan, 50% of students in 2021 felt instructors showed discomfort or lack of familiarity with required technologies, and this figure remained largely unchanged in 2022, decreasing by only 1% (UBC Okanagan, 2021; UBC Okanagan 2022). These challenges were more pronounced among domestic students, who consistently reported higher levels of instructor discomfort compared to their international peers. For example, in 2022, 51% of domestic students and 33% of international students noted instructor discomfort with required technologies (UBC Okanagan, 2022). Faculty familiarity with digital tools varied across campuses and technologies. When asked whether “faculty at [their] institution have the skills and know-how to effectively teach” different modalities, only 12% of faculty respondents believed all or most instructors were competent with multi-access technologies, while 39% felt some faculty could use these tools effectively (Canadian Digital Learning Research Association, 2023).

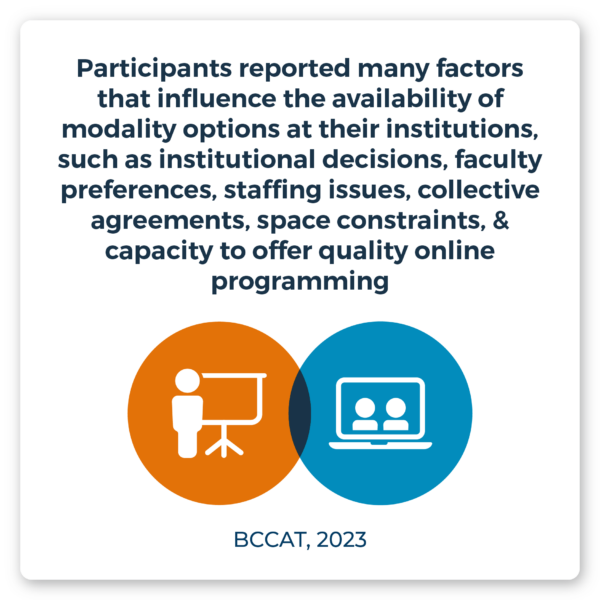

Institutional Flexibility and Adaptivity

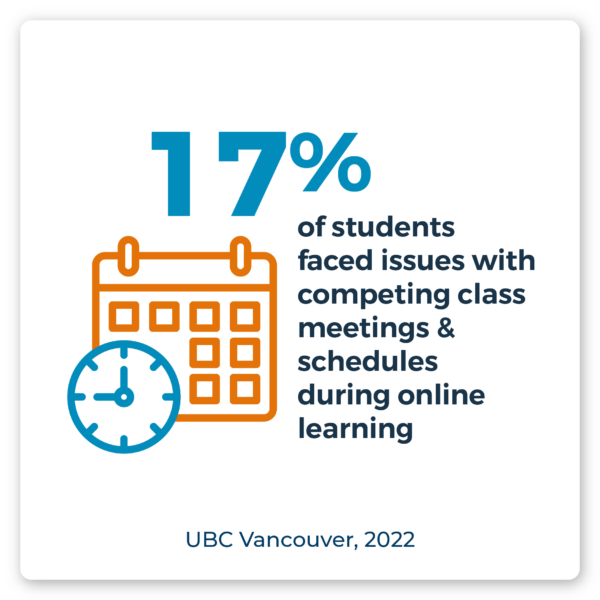

The Canadian Digital Learning Research Association noted that “professional development for faculty is mostly voluntary, regardless of course delivery mode” (Canadian Digital Learning Research Association, 2023). Institutions made strides in addressing course availability and adapting to student needs. For example, an institution in BC reported that students expressed concern about course scheduling and availability, while appreciating the institution’s efforts to ensure continuity of education.

Additionally, Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles are increasingly recommended for course delivery and design. In a post-pandemic study of first-year Ontario students, Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario (2022a) recommended the integration of “Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles in all courses“ (p. 5). Providing multiple learning formats empowers students to select options that align with their unique learning preferences and needs.

Technology

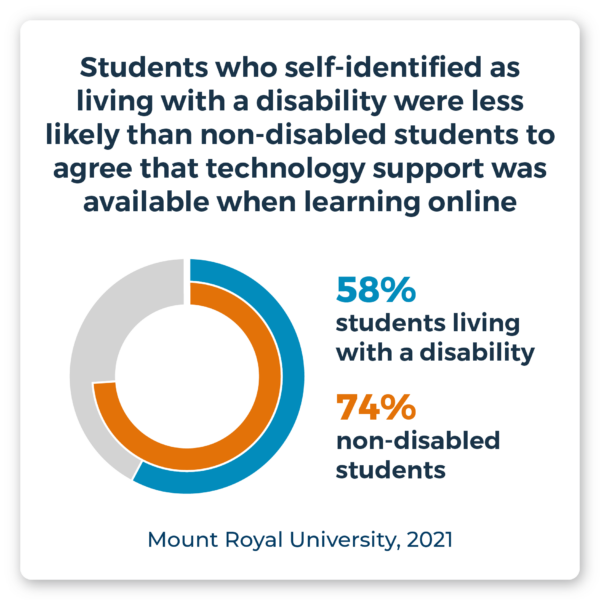

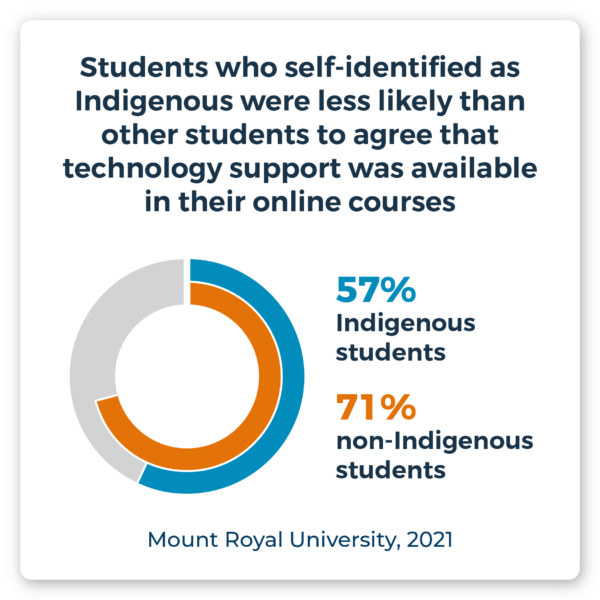

Despite its benefits, online learning posed significant challenges. Technological barriers disproportionately affected low-income and rural students, with many reported difficulties accessing reliable internet or adequate devices. Studies have shown that students with unreliable internet or outdated devices reported feeling left behind in their studies due to technological inequities (Ontario Undergraduate Student Alliance, 2020).

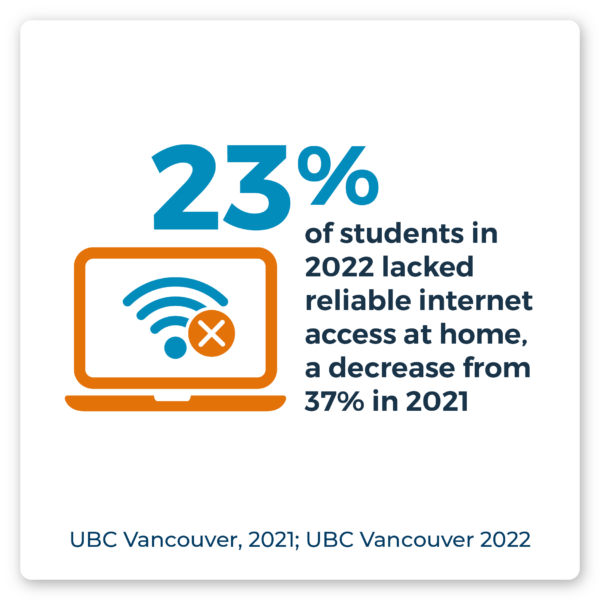

Access to reliable technology and internet emerged as a critical issue during the transition to online learning. At UBC Vancouver, 37% of students lacked reliable internet service at home in 2021, but this figure dropped to 23% by 2022 (UBC Vancouver, 2022). Similarly, at UBC Okanagan, 35% of students lacked access to reliable internet service in 2021. In 2022, 21% reported lacking access to reliable internet service on-campus (UBC Okanagan, 2022).

To reduce gaps in high-speed internet access highlighted during the pandemic, Canada has launched a program to ensure all Canadians are connected by 2030 (Loprespub, 2021). The improvements to high-speed internet infrastructure could lead to reduced barriers to online learning, particularly for Indigenous post-secondary students in remote communities (Indspire, 2020).

Other innovations, such as Yukon University’s Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) initiative provided some flexibility, yet financial barriers persisted, limiting the program’s effectiveness for some students (Yukon University, 2021). Students also reported challenges beyond internet access, including limited availability of reliable devices, specialized software, and communication tools.

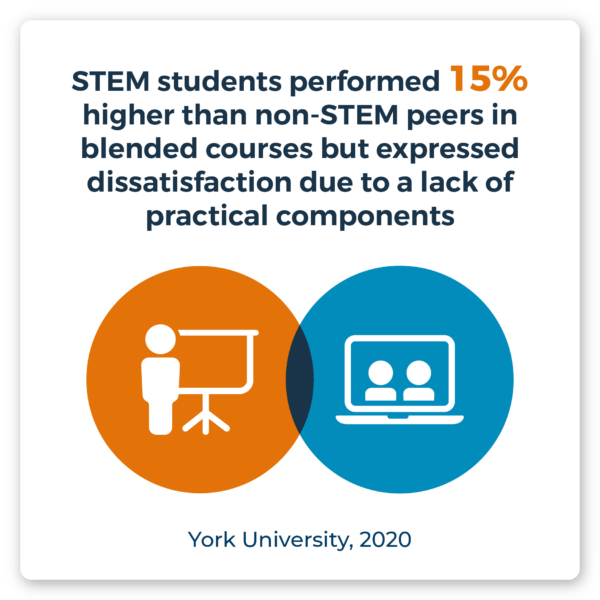

Blended learning, which combines online resources with in-person activities, has emerged as a particularly effective model for STEM disciplines (York University, 2020). This approach allows students to benefit from the flexibility of digital tools while retaining the critical experiential components of their education. However, the transition to blended learning requires a fundamental rethinking of course design to achieve optimal outcomes.

Student Experience

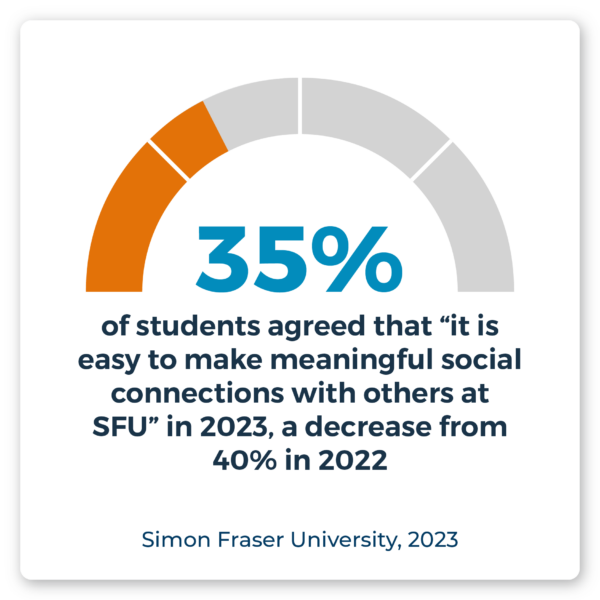

Social Connection

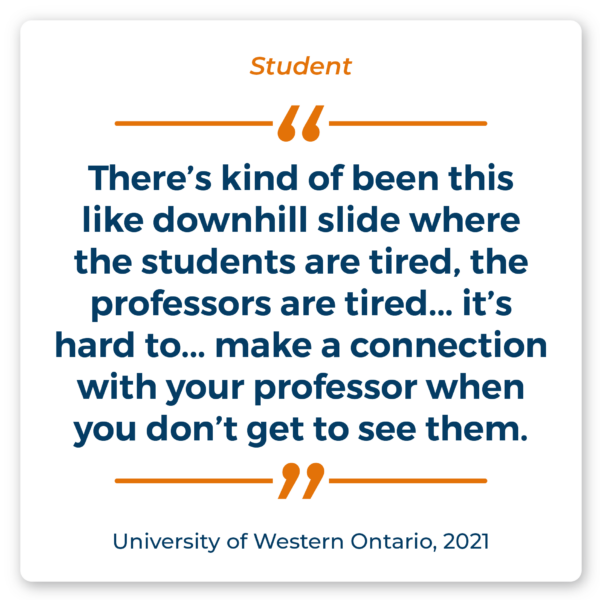

In addition to technological barriers, students frequently encounter broader systemic challenges in online learning environments. The pandemic disrupted formal and informal learning communities, highlighting the need to prioritize social connections in academic settings. As Western University (2021) observed, the disruption of learning communities during the transition to online education underscores the importance of fostering both formal and informal networks in academic settings. Future course delivery models should integrate opportunities for interaction and collaboration to rebuild these communities and enhance the overall learning experience.

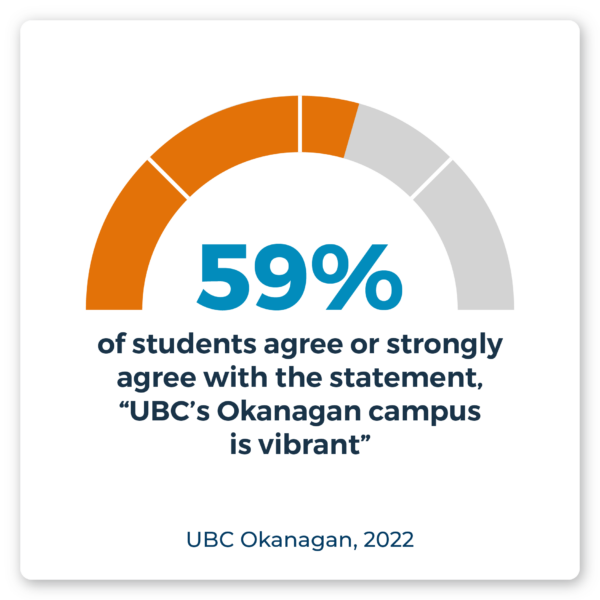

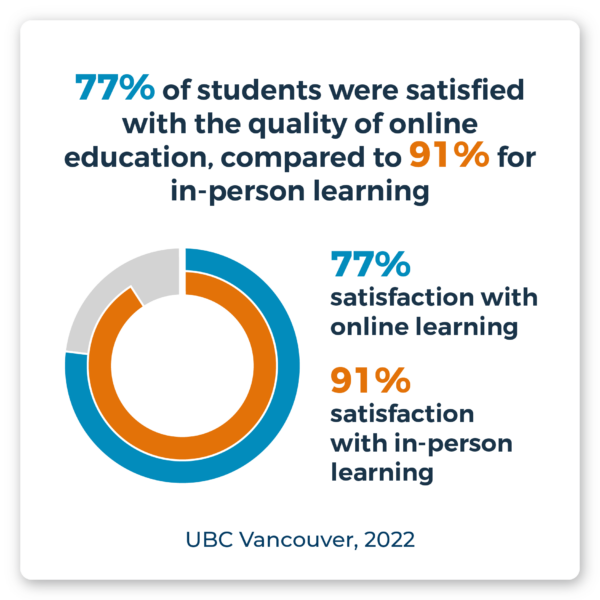

Student Well Being and Satisfaction

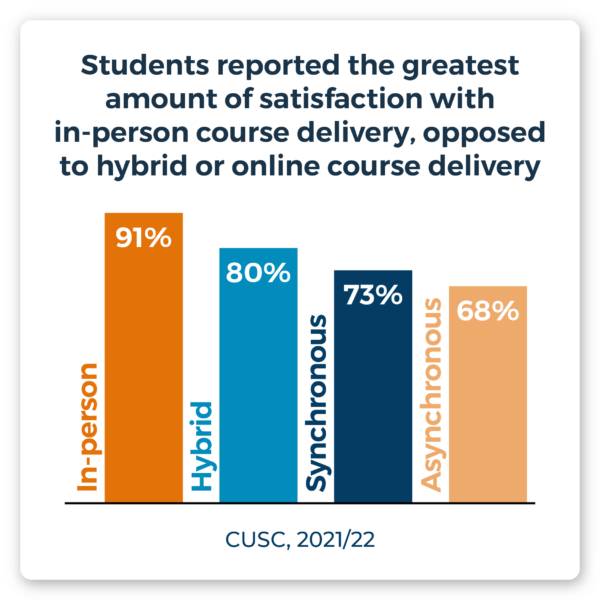

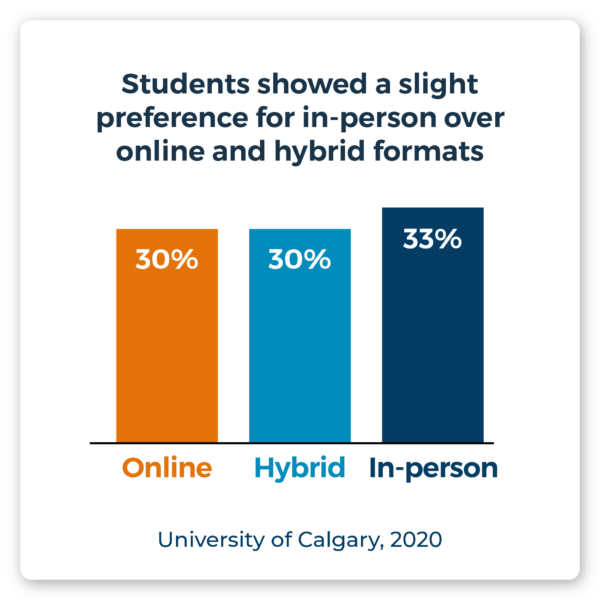

Hybrid models gained significant traction across institutions as a preferred solution, combining the flexibility of online learning with the engagement of in-person instruction. At Mount Royal University, “about one in two students (52%) said they would prefer to have their online courses taught with a hybrid of synchronous and asynchronous delivery methods” (Mount Royal University, 2021).

The lack of in-person interaction during online learning created significant obstacles in building communities of learning. According to focus group participants at Western University, students cited burnout and limited interpersonal connections as major challenges in the online environment. They found that the absence of informal networks and peer-to-peer engagement compounded feelings of isolation and reduced overall satisfaction (Western University, 2021).

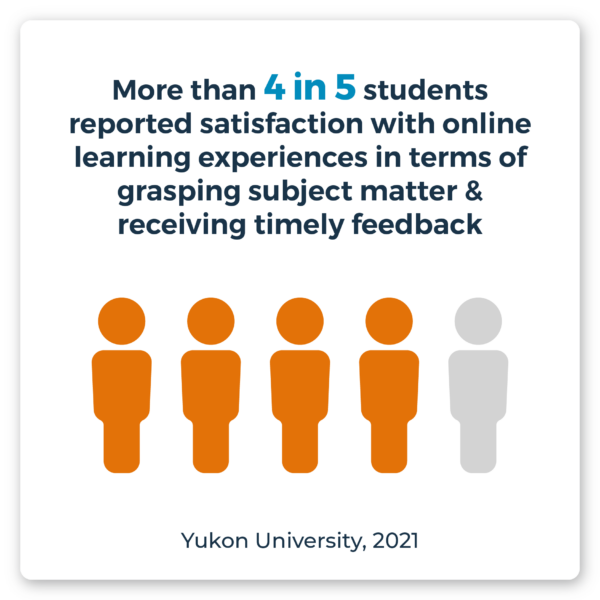

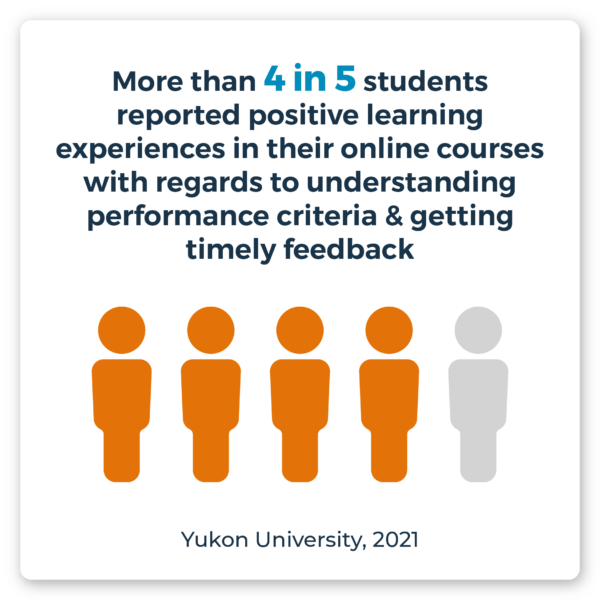

At other schools, there were more positive results reported. Yukon University found that “more than four out of five students reported positive online learning experiences”, and “close to nine out of ten students (88%) agree or strongly agree that they are getting a good grasp of the subject matter in their online courses” (Yukon University, 2021).

Student Engagement

Student Performance

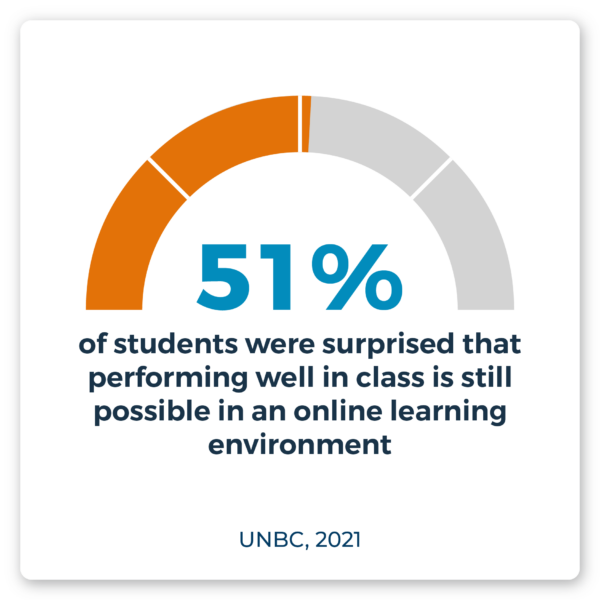

It has been repeatedly reported that there is a “positive relationship between student engagement and academic performance at the post-secondary level” (Mount Allison University, 2021, p.2). Many studies to date have explored the impacts of various course modalities on student engagement and thus, academic performance. For example, Akpen et al. (2024) found varied results through their systematic review of studies exploring the impacts of online learning on academic performance. Some studies reported “increased performance due to the flexibility and accessibility of online learning,” while others reported “challenges such as decreased engagement and isolation,” which contributed to reduced academic performance (Akpen et al., 2024). Further, Ontario Undergraduate Student Alliance (2020) found that students with better access to technology (e.g., fast and reliable internet) would perform better academically as they would study more frequently and obtain higher grades.

Interestingly, some studies have found that academic performance in blended learning environments is often impacted by the type of course a student is enrolled in. For example, one study noted that, in blended learning environments, “STEM students performed significantly higher than non-STEM students; however, STEM students did not perceive their courses as positively as non-STEM students” (York University, 2020).

Student Focus and Motivation

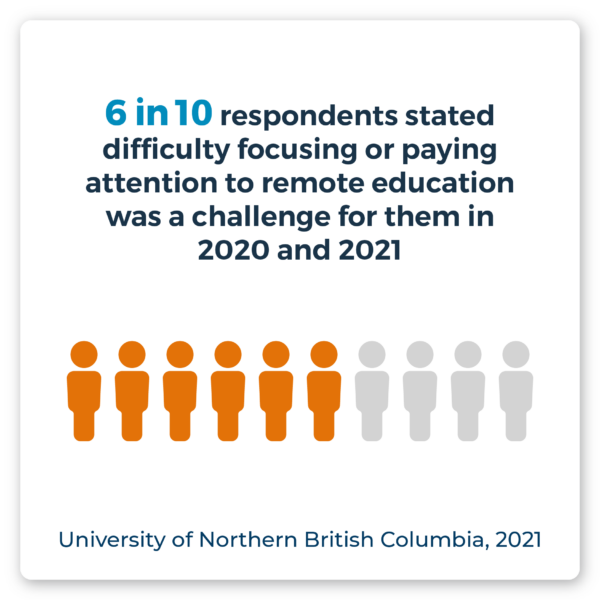

Post-secondary students’ ability to focus, and their motivation to study, varies drastically depending on the modality in which they are taking a course (Filak & Nicolini, 2018). At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the online learning environment presented significant challenges related to student focus and motivation. For example, the University of Toronto (2021) identified a lack of motivation to learn as one of the nine greatest barriers students faced related to online learning. Further, University of Calgary (2020) found that amidst the solely online learning environment (i.e., 2020) 7% of respondents indicated that motivational supports would be the most impactful support the University of Calgary could provide to help them be successful in their semester.

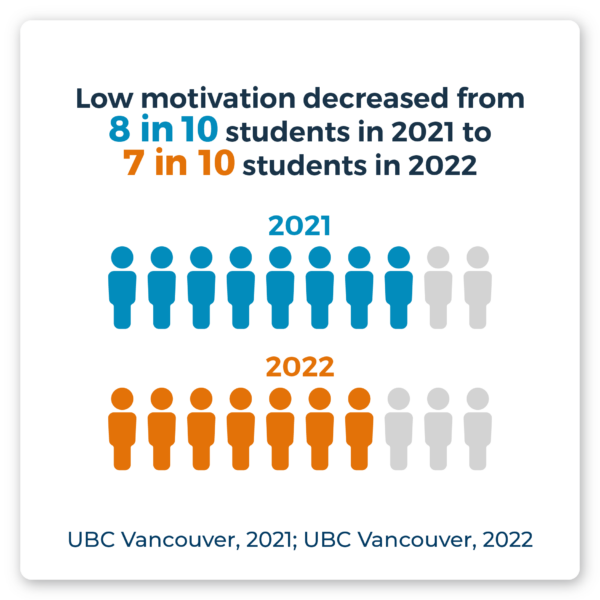

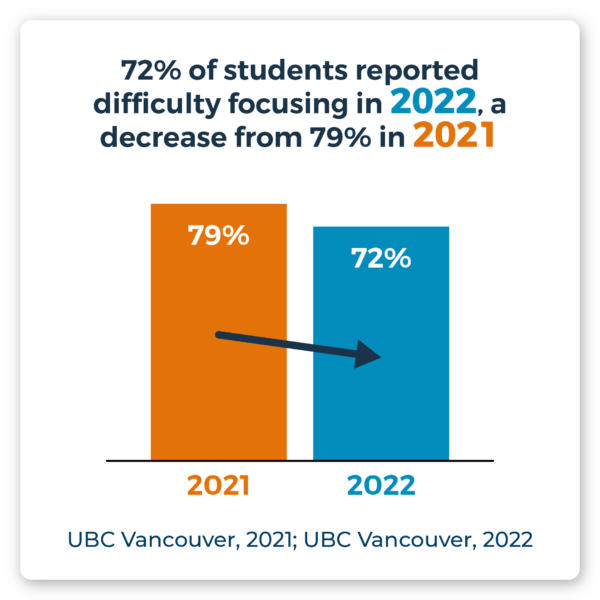

However, interestingly, over the following years these challenges seemed to be less apparent. For example, students at UBC Vancouver and UBC Okanagan experienced gradual improvements in their ability to manage online learning challenges between 2021 and 2022. At UBC Vancouver, the percentage of students reporting difficulty focusing dropped from 79% in 2021 to 72% in 2022, while low motivation decreased from 78% to 69% (UBC Vancouver 2021; UBC Vancouver, 2022). Similarly, at UBC Okanagan, difficulty focusing reduced from 77% to 75%, and low motivation declined from 75% to 73% during the same period (UBC Okanagan, 2021; UBC Okanagan, 2022).

Student Flexibility

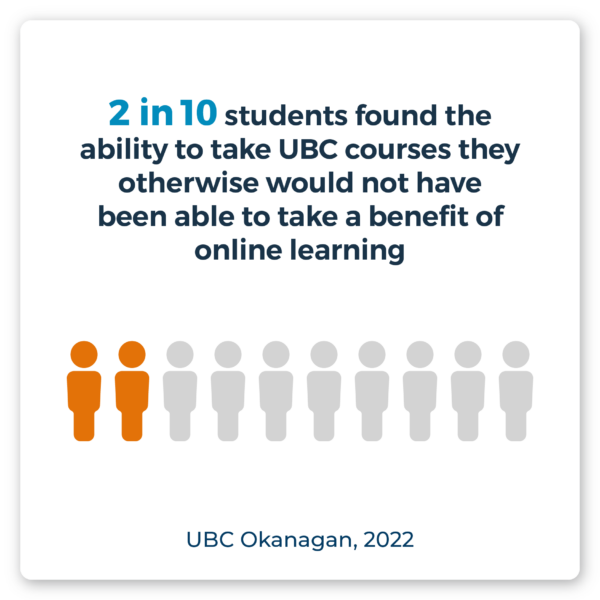

Although there are varying benefits to each type of course modality in terms of flexibility, online and hybrid learning often prevail as the modalities that provide students with the most flexibility. Online and hybrid learning allow students greater ability to balance academic, work, and caregiving responsibilities. Furthermore, online and hybrid learning often allow students the ability to access materials asynchronously and the ability to study at their own pace. For marginalized students, online learning can reduce barriers to education (such as commuting) and can facilitate easier access to accommodations. For example, for some students, online learning enabled them to navigate accommodations more anonymously, reducing stigma and allowing them to engage more fully in their education (Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario, 2020).

Students’ preferences for synchronous and asynchronous formats varies based on individual needs and circumstances. In UBC Okanagan’s 2021 survey, 78% of students valued the ability to pause online lectures, and 57% found it beneficial to avoid commuting or move to live near campus (UBC Okanagan, 2021). Similarly, many students at UBC Vancouver reported that online class availability allows them to enroll in courses they otherwise would not have been able to access (UBC Vancouver, 2022).

Flexibility in course delivery has become a priority for students navigating academic and personal responsibilities. When institutions offer multiple learning modalities, students can choose formats that best suit their needs. According to the Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario (2022b), students report improved ability to balance academic and personal responsibilities when given access to multiple delivery modes. This adaptability empowers students to tailor their educational experiences, enhancing engagement and success.

References

Full Reference List

Akpen, C. Nc, Asaolu, S., Atobatele, S. Okagbye, H., & Sampson, S. (2024). Impact of online learning on student’s performance and engagement: A systematic review. Discover Education, 3(205). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44217-024-00253-0

Canadian Digital Learning Research Association (CDLRA). (2023). An Increasing Demand for Technology Use in Teaching and Learning: 2023 Pan-Canadian Report on Digital Learning Trends in Canadian Post-Secondary Education. Link

Filak, V. F., & Nicolini, K. M. (2018). Differentiations in motivation and need satisfaction based on course modality: a self-determination theory perspective. Educational Psychology, 38(6), 772–784. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2018.1457776

Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario. (2020). Improving the Accessibility of Remote Higher Education: Lessons from the Pandemic and Recommendations. Link

Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario. (2022a). Ontario Learning During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Experiences of Ontario First-year Postsecondary Students in 2020–21. Link

Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario. (2022b). Ontario Learning Since the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Updated Look at Student Experiences and Outcomes in 2021–2022. Link

Indspire. (2020). Indigenous Post-Secondary Learners and COVID-19 Pandemic. Indspire Research Knowledge Nest. Link

Loprespub. (2021). Broadband Internet in Indigenous Communities. HillNotes. Link

Mount Allison University. (2021). Student engagement across course teaching modalities. Link

Mount Royal University. (2021). Winter 2021: student COVID impact survey results. Link

Ontario Undergraduate Student Alliance (OUSA). (2020). Accessibility: results from the 2020 Ontario undergraduate student survey. Link

University of British Columbia Okanagan. (2021). Undergraduate experience survey 2021: Full distribution report. Okanagan Campus. Link

University of British Columbia Okanagan. (2022). Undergraduate experience survey 2022: Full distribution report. Okanagan Campus. Link

University of British Columbia Vancouver. (2021). Undergraduate experience survey 2021: Full distribution report. Vancouver Campus. Link

University of British Columbia Vancouver. (2022). Undergraduate experience survey 2022: Full distribution report. Vancouver Campus. Link

University of Calgary. (2020). Fall 2020 survey results. Link

Western University. (2021). Lessons from Zoom-university: Post-secondary student consequences and coping during the COVID-19 pandemic—A focus group study. Link

York University. (2020). Blended learning in STEM and non-STEM courses: How do student performance and perceptions compare? Online Learning Journal, 24(3), 203–221. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v24i3.2151

Yukon University. (2021). Yukon University student survey results: 2021. Link